UceniKoin.

I love blockchain technology. It's so simple yet so elegant that I'm mad at myself for never having implemented it on my own. That has to change.

Intro

Today I'm implementing my own cryptocurrency by reading the Bitcoin whitepaper . I'm not going to explain why the Bitcoin protocol is safe, as I think that is well covered by people like Grant Sanderson from 3Blue1Brown . I am however going to explain the more technical aspects, diving right into some code so we can appreciate the full picture without simplifications that use the word "gold".

Anyway, as always, I'm going for Pareto's principle so don't expect a finished product. I'm implementing the basic concepts as a didactic introduction, and you can find all of what I'll be showing in this repo . Let's get going.

Money

- People have things.

- People need things other people have.

- Not all things are equally valuable.

These premises are the motivation for creating an entity which quantizes value and allows for it to be exchanged for other things with equal value. That entity is money.

I'm no economist/philosopher, so I won't get into why money is valuable. For simplicity's sake, let's just say money is something that belongs to someone and that can be transferred.

Exchanging and Signatures

For money to go from owner A to another owner B, there must be a system in place to verify that owner A indeed wants to send that money to owner B. During a long time, that system was physical presence: handing commodities in person. With digital banking it becomes a matter of sending a request to your commercial bank. The advent of cryptography lends us a new way of confirming ownership: digital signatures.

Public-Key Cryptography

If you understand Public-key cryptography , skip this section.

In essence, everyone must have both a public key and a private key. A "key" is just text . You can represent it as bytes, as characters or as a QR code. Each person identifies themselves with their public key. Want to see mine? Here it is:

The public key is useless by itself (anyone could just copy it and claim they're me). That's why we need a private key next to it. To be clear: private keys must NOT be shared, that's why they're also called "secret".

Signing

Keypairs define a set of operations, one of which is signing. In the real world, signing is whatever you do to prove that something was done by you. You may write your typographical signature in a contract, or carve your name with a penknife on a door, or leave your fingerprint in ink. In the digital world, any of these signatures is subject to forgery, as any data you write can be copied indefinitely. You must imagine a digital signature as a function that takes in a message and the private key of whoever writes it and outputs some garbage:

\[\textrm{Sign(Message, Secret key) = Output}\]

So for example \(\text{Sign(“Hello!”, “123") = “1S4KKW5AUF"}\) . One property of this is that that message next to that private key will always produce that same output , but even a minute variation to any of them will produce a completely different output. The output in question is what we call the signature.

The private key is fundamentally linked to the public key, so this signature can be validated by other people using another function that takes in the signer's public key, the message and the signature and outputs whether the signature is valid or not:

\[\textrm{Verify(Signature, Message, Public key) = Output}\]

One might think that by knowing whether a signature is valid or not, then one can freely forge signatures by trial and error. This is true, but in practice it takes so much time that it's never done (we are talking extra-cosmic scales). We have no proof that it's impossible to construct a \(\textrm{Sign}^{-1}\) function, but modern security relies on the fact that it is.

Transactions

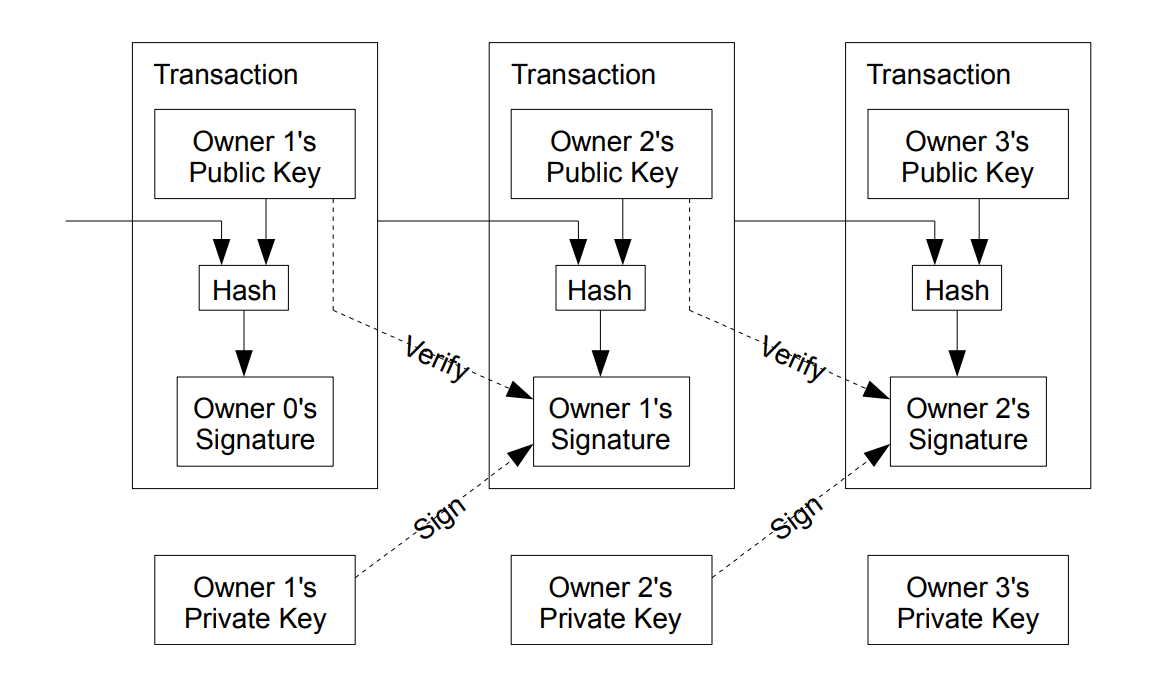

We were talking about a system to verify ownership over money using digital signatures, and this is such system. According to the Bitcoin protocol, when owner A wants to send money to owner B, he will:

- Write down the public key of owner B.

- Write down the amount to be sent (kinda).

- Sign the message with his private key.

Put together, those operations conform a transaction .

When owner A creates a transaction, they broadcast it to nodes and those nodes put them into blocks . How this process is decentralized without generating ambiguity and preventing double-spending is what the Bitcoin Whitepaper addresses through Proof of Work , and it will be explained when dealing with the code.

Units

You might be wondering about units. What would "20 UceniKoin" exactly mean in a transaction like the one described? How much would it be worth? If we stick to raw math, the question is meaningless. UceniKoin is just the unit that this system uses. Maybe Alice sends 20 Koins to me in exchange for me giving her $40 in real life. Does that mean that each Koin is worth $2? Well maybe, but then Bob and Eve might exchange 20 Koins for $1. A price is just an average of all existing exchange rates. At least that's how I view it, actual economists might differ and I'll be glad to listen.

Hashes

Unrelated to the previous sections but nonetheless important to our objective. A hash function is a function that takes in a message and produces an output. Just like with signatures, the same message will produce the same output. There are many hash functions, but the one we'll be using is SHA256() .

\[\textrm{Hash(Text) = Output}\]

UceniKoin's Code

I think the following concepts are better explained by looking the code in the eyes.

Wallets

We are going to need a bunch of objects, starting with wallets. A wallet is a wrapper for a keypair (see Public-Key Cryptography). I will store keypairs as their PEM export, that way it'll be easier to transfer them through the Internet.

class Wallet:

pk: str

sk: str

def __init__(self, keypair_name):

with open(f"{keypair_name}_pk.pem", "r") as fpk, open(f"{keypair_name}_sk.pem", "r") as fsk:

self.pk, self.sk = (fpk.read(), fsk.read())

Transactions

As explained before, a transaction comprises the receiver's public

key and the sender's signature of the transaction. Each transaction must

be uniquely identified to not be copy-pasted, so we'll also throw in a

uuid

.

class Transaction:

uuid: str

payer_signature: str

payer_pk: str

payee_pk: str

amount: int

To sign this transaction, we'll have to convert it to a bytes format. I think a reasonable way to do this is to convert the Transaction object into a dict and then transform the dict into a JSON.

def to_dict(self) -> dict:

return vars(self)

def to_JSON(self) -> str:

return json.dumps(self.to_dict())

Now we can sign the transaction. RSA needs to work in bytes, so we

will

encode

the string to

utf-8

.

rsa_payer_sk = rsa.PrivateKey.load_pkcs1(payer_sk)

transaction_json = self.to_JSON().encode('utf-8')

self.payer_signature = rsa.sign(transaction_json, rsa_payer_sk, hash_method="SHA-256").hex()

Now that we have transactions, we can use our wallet to create them and broadcast them to all nodes.

def send(self, payee_pk: str, amount: int):

transaction = Transaction(self.pk, self.sk, payee_pk, amount)

broadcast(transaction)

Blocks

We will go into the broadcasting process when we get to nodes, but

before that let's not forget that we still haven't created our

Block

class. A block is just a list of transactions. Each

block has a timestamp to identify when it was created and contains its

own hash and the hash of the previous block. Because of this last

detail, each block references another block, and so they can be

organized in a chain: the

blockchain(s)

.

To ensure consensus, the Bitcoin protocol specifies that hashes have to start with a given number of zeros to be accepted as valid. This is Proof of Work, as obtaining that hash requires computational work. PoW allows the network to agree on the correct blockchain: it'll be the one with the most work put into it. To be able to get different hashes we vary an attribute of the Block called the "nonce" (number used once) until the hash is OK.

class Block:

nonce: int

timestamp: float

prev_hash: str

hash: str

transactions: list[Transaction]

Changing that nonce until getting a hash that starts with the correct number of zeros is called "mining". I've done this by counting up, which isn't a good way. In reality you would want to generate these nonce randomly.

def mine(self):

while True:

block_json = self.to_JSON().encode('utf-8')

hash = hashlib.sha256(block_json).hexdigest()

if hash.startswith("00"):

self.hash = hash

return hash

else:

self.nonce += 1

Note that the protocol defines how many zeros are necessary to consider a block as valid, and that determines how hard it is to produce a block. Most protocols (including Bitcoin's) vary this amount by making it proportional to the hashing rate of the network (how quickly can miners check for nonces). I will arbitrarily set it to two zeros.

Blockchains

Finally, blockchains. We can define a blockchain just by its head, as that head will reference another block, which will reference another block, and so on. We call the set of all blocks "the blockpool". Note, there can be many blockchains on the same pool (see the Final thoughts section).

The pool will be stored by nodes as a list and sent to clients when needed. If you have the head, you can navigate the chain and find the balance of each wallet. The actual Bitcoin protocol and others like Monero might beg to differ, but hey, we agreed to keep it simple. No Merkle trees in here.

class Blockchain:

head: Block

And that's pretty much it for this file . I have left out some functions to convert to-and-fro JSON, but in essence we are done.

Clients

All the client has to do is:

- Make transactions.

- Broadcast transactions.

The client could make invalid transactions, like sending more than he has or forging invalid signatures, but those transactions would just get rejected by nodes. (I haven't actually programmed all of the checking, but I think you get the gist of it.)

Let's say Alice wants to send me some money. Assuming she has already created her keypair, then she just needs my public key.

alice_wallet = Wallet("./keys/alice")

with open("./keys/erik_pk.pem", "rb") as f:

erik_pk = rsa.PublicKey.load_pkcs1(f.read())

alice_wallet.send(erik_pk, 20)

Remember the

broadcast()

function? This is when it comes

into place. Alice's transaction has to be collected by some node for it

to be incorporated into a block. That's what

broadcast

does.

def broadcast(transaction: Transaction):

json = transaction.to_dict()

requests.post("http://localhost:6661/tx", json=json)

requests.post("http://localhost:6662/tx", json=json)

In reality you would want to access some sort of website that gave you a list of all nodes currently running in the network. Node runners would ask those websites to upload the addresses of their nodes such that they could receive mining fees and block rewards.

That's it for client.py . Onto the actual brains.

Nodes

As with clients, nodes have four simple tasks:

- Collecting transactions.

- Making blocks.

- Finding a valid hash for those blocks (aka "mining").

- Broadcasting the brand-new blocks to other nodes.

Let's add a final one for completeness sake:

- Listen to broadcasted blocks from other nodes.

Setup

Every node starts with a genesis block which they manually mine. Here we are assuming that all nodes begin to run at the same time and keep running perpetually. As always, reality is more complex. You would want to be able to incorporate new nodes into the network, so nodes would have to be able to ask other nodes for their blockchains.

head = Block("0")

blockchain = Blockchain(head)

transaction_queue: list[Transaction] = []

blockchains: list[Blockchain] = [blockchain]

blockpool: list[Block] = [head]

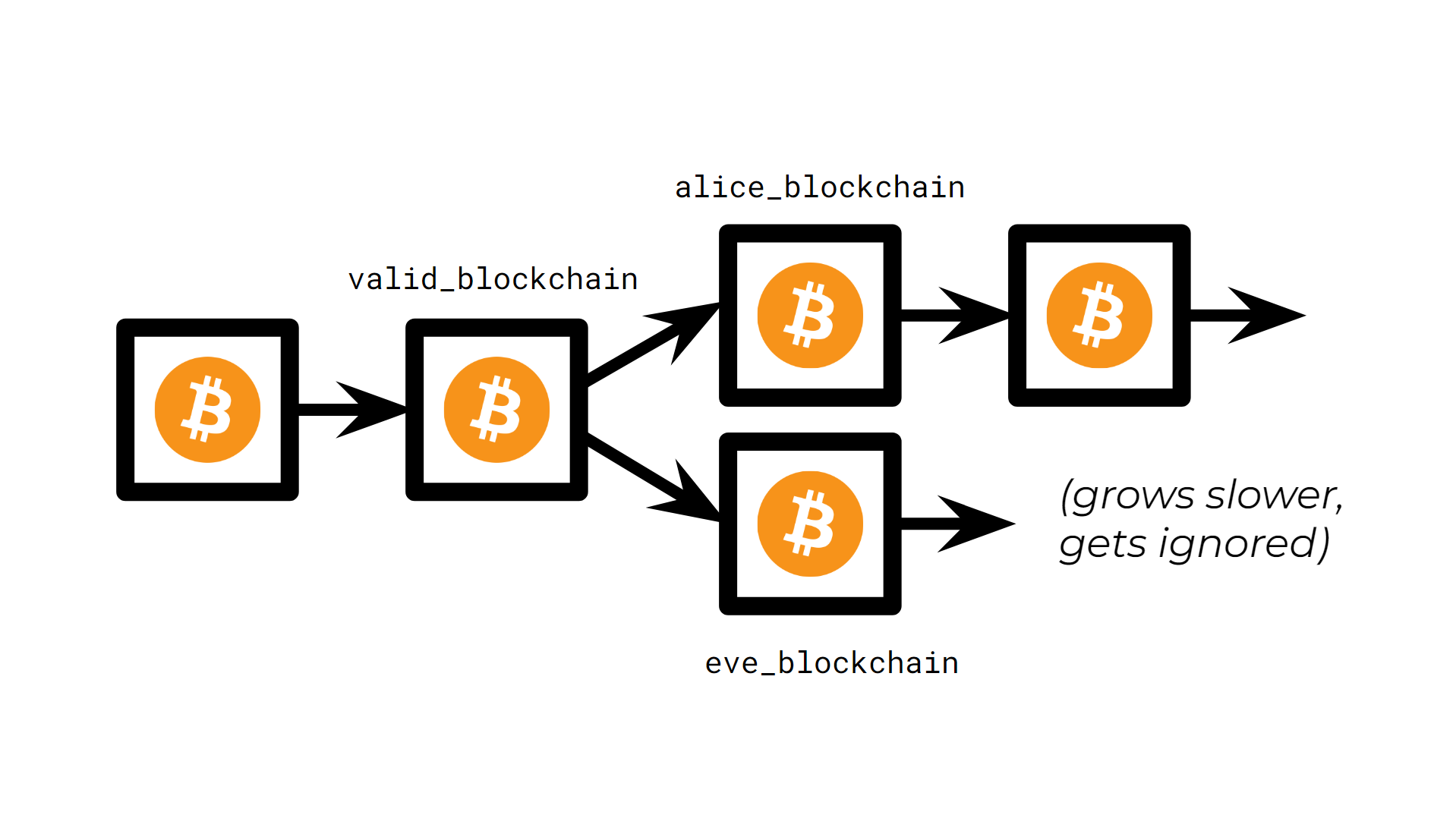

The purpose of the

blockchains

variable is to store

conflicting blockchains. For example, if we had just one blockchain,

then that variable would look like

blockchains = [valid_blockchain]

. Now imagine Alice

broadcasts a good block, whereas Eve broadcasts a malicious one. A

bifurcation would occur, leaving the last block of our original

blockchain being pointed at by two different blocks. In this case,

blockchains = [alice_blockchain, eve_blockchain]

(where

each blockchain would have Alice's and Eve's blocks as their head

respectively). The hash of each head is different, so each blockchain is

going to grow independently. However, thanks to the proof-of-work

system, growing the malicious chain is going to be unsustainable in

terms of computing power (once again, see

3B1B's

explanation

). Eventually Eve's blockchain will be so short in

comparison that it will just be ignored.

Each node listens to incoming transactions and places them on a queue (a list). Once the list reaches the maximum block size (which we have set to be 5 transactions), a block is created, added to the blockchain and broadcasted to other nodes. To listen to incoming blocks and transactions we'll be using FastAPI.

app = FastAPI()

@app.post("/tx")

async def receive_transaction(request: Request):

tx_json = await request.json()

transaction = Transaction().from_JSON(tx_json)

transaction_queue.append(transaction)

if len(transaction_queue) == 5:

block = create_block()

add_created_block_to_blockchains(block)

broadcast(block)

I think you can guess what the

create_block()

function

looks like.

def create_block() -> Block:

global head, transaction_queue

block = Block(head.hash)

block.add_transactions(transaction_queue)

block.mine()

return block

The mining process should possibly be implemented in some sort of asyncronous way. That way, if other node finds a valid hash before you do, then you can stop the mining and incorporate that block.

Broadcasting blocks follows the same principle as broadcasting transactions. You would probably want a list of running nodes and have some code to avoid sending the block to yourself (although it would be filtered as an invalid block so it's not a big deal), but then again, in our example it's hardcoded.

def broadcast(block: Block) -> None:

json = block.to_dict()

request.post("http://localhost:6662/block", json=json)

Of course as nodes we have to be able to listen to incoming blocks. When we receive a block we add it to the blockpool and check whether it points to the head of an existing blockchain. If it doesn't, it gets to be the head of a new blockchain.

@app.post("/block")

async def receive_block(request: Request) -> None:

block_json = await request.json()

block = Block("0").from_JSON(block_json)

blockpool.append(block)

for blockchain in blockchains:

if blockchain.head.hash == block.prev_hash:

blockchain.head = block

return

blockchain = Blockchain(block)

blockchains.append(blockchain)

Here comes another simplification. The block we've received may

contain transactions already in our

transaction_queue

. To

not have them duplicated, it is good to remove them from the queue. The

way we do this is with the following line:

transaction_queue = []

However, the transactions in the block may not coincide with the

transactions in our queue. The correct way to do this would be to check

the IDs of the transactions to know which ones to remove and which not

to. But this is not enough. There might be transactions in the block

that are not present in our queue nor in any block already in our node's

blockpool. In that case the IDs of those transactions should be stored

in some sort of

ignore

list such that when they arrived to

us, they weren't double-processed. Again, if the node checks for unique

IDs, it won't be a problem anyway.

Finally, let's add an endpoint to send the blockchains and full

blockpool in our node to whoever requests it. This is what

client.py

could use to get the blockchain and check their

balances.

@app.get("/blockchains")

async def send_blockchains():

global blockchains, blockpool

blockchains_dicts_list = [blockchain.to_dict() for blockchain in blockchains]

blockpool_dict = [block.to_dict() for block in blockpool]

return { 'blockpool': blockpool_dict, 'blockchains': blockchains_dicts_list }

Final thoughts

You've seen the code, you've seen the problems, but at least I think you have gotten a gist of the low level landscape of the Bitcoin protocol. UceniKoin isn't even close to safe, I think it's barely functional, but it serves the purpose of showcasing the meaning of grandiloquent words used day in and day out in the news and finance circles. A few examples:

-

One of the main implementations of actual Bitcoin (and not some

random UceniKoin) is

Bitcoin Core

. You can

install it in your own computer (see instructions in

doc/build-*.md). It comes with a daemon and its own GUI wallet. I will warn you that the blockchain is about 600 GB long. - We've mentioned the need for nodes to be able to find each other. This is managed with DNS seeds: a series of hostnames that contain a list of the IP addresses of running nodes. DNS seeds are actually hardcoded, and you can find them here .

-

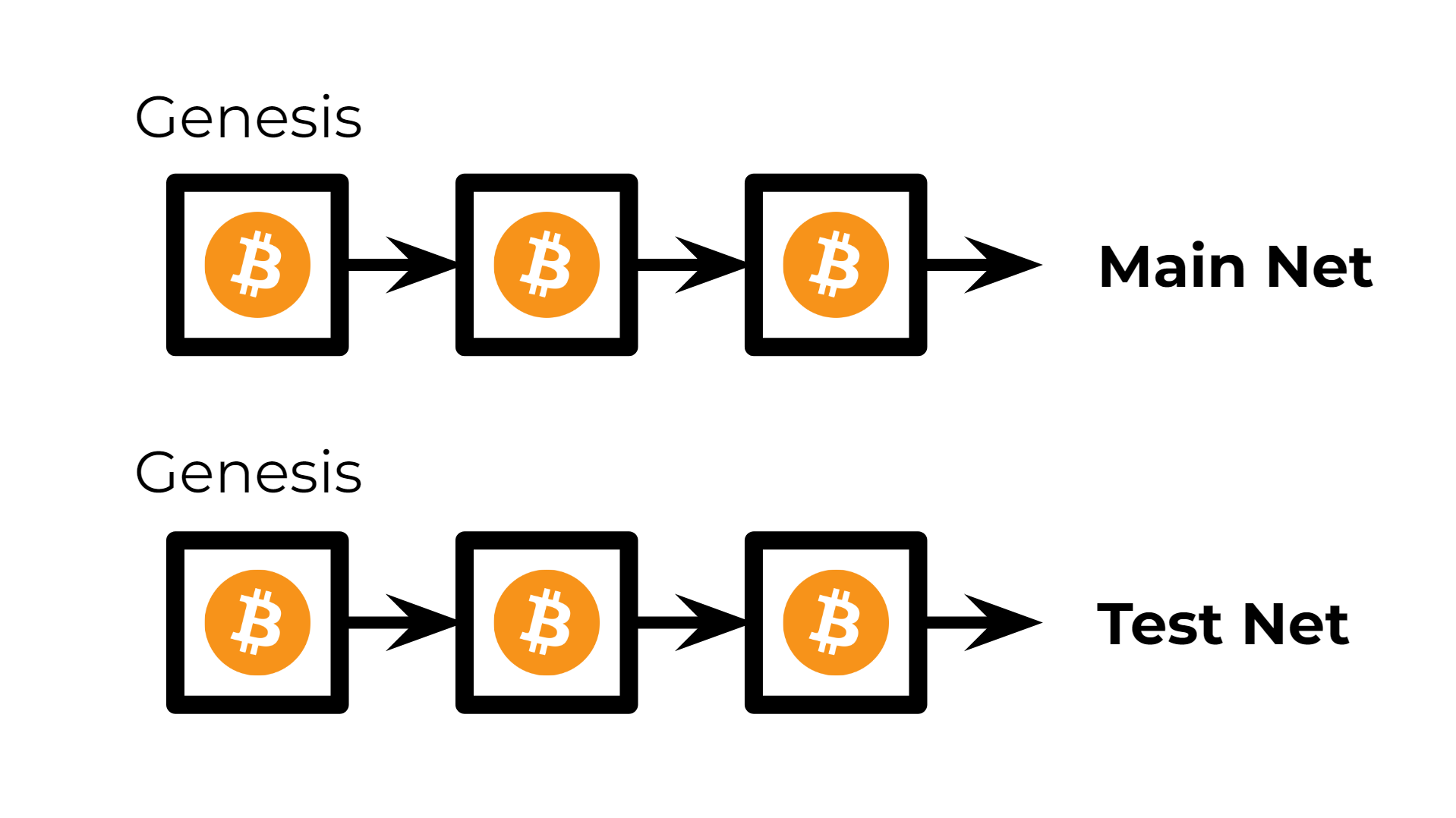

Ever heard of the Bitcoin "testnet"? Turns out its just another

blockchainvariable! Through this article we've used theblockchainslist as an index of the existing and conflicting branches of a common blockchain. They were all different, but they shared the same "backbone" and they all started on the same genesis block. A testnet however is an altogether different blockchain. Its transactions are completely unrelated to the ones in the "mainnet" and they start on a different genesis block. The testnet is basically used by developers of Bitcoin to try out new features and experiment with the protocol. As you'll understand, devs wouldn't be too fond of trying out new things in an active network with millions of dollars in circulation.

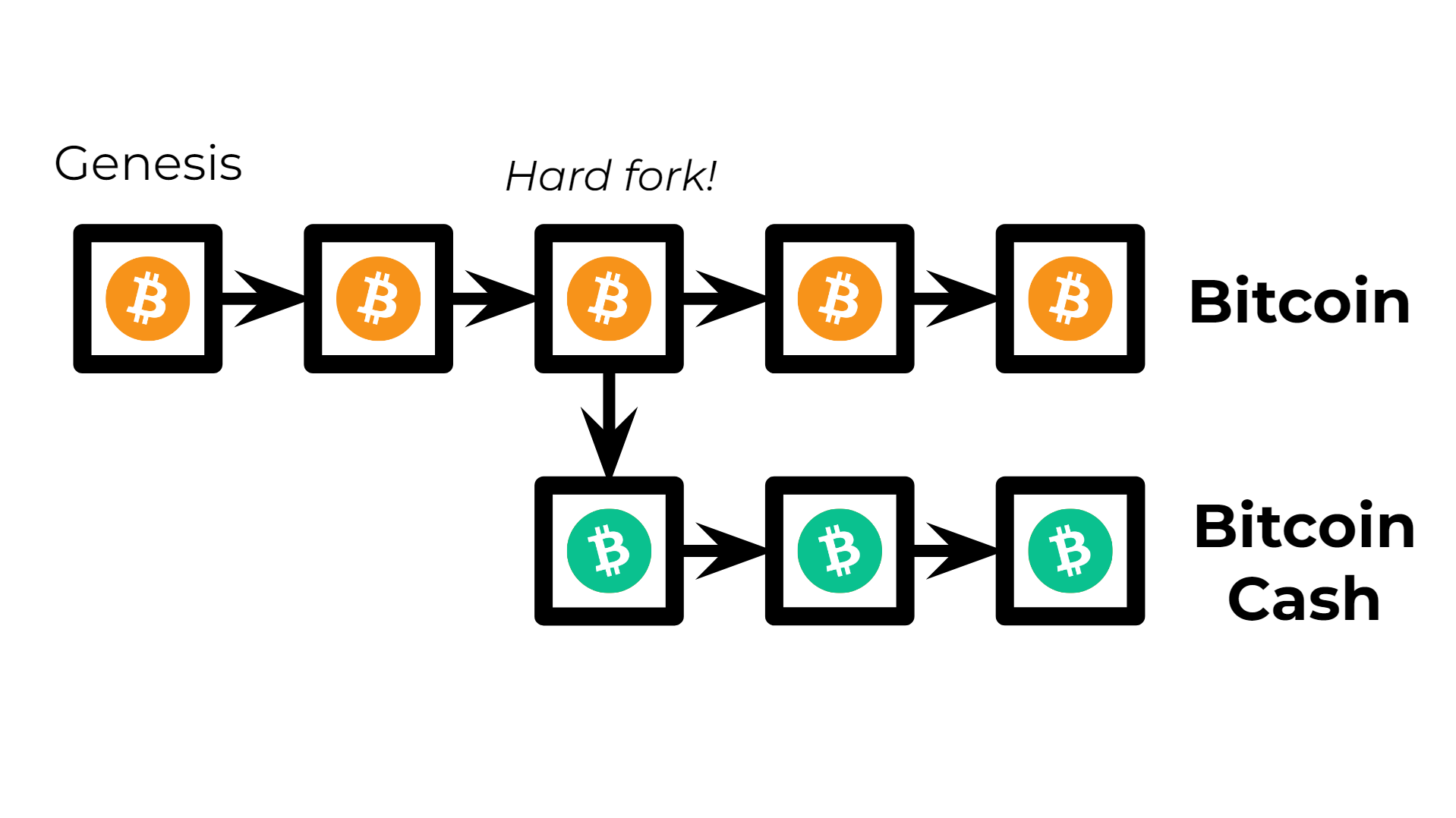

- There's a similar concept to this known as forks, which can be hard or soft. Remember Eve trying to sneak up evil blocks? Well, sometimes a community intentionally does this and sticks to the newer, shorter blockchain instead. Usually this is done to implement a change in the protocol. For example, some people considered the Bitcoin blockchain to be too slow, so they implemented a protocol pretty much identical to the original, but changing the amount of transactions per block from 2.000 to 25.000. This fork was followed by some people, who accepted the blocks of the new protocol and made a new blockchain, but not by others, who stuck around with the original blockchain, accepting only the blocks that followed Bitcoin's original protocol. Now imagine you want to exchange some bitcoin with your friend. Which chain would you append your block to? If you had to buy some bitcoin, would you buy from a seller whose transaction is valid on the original Bitcoin blockchain or from one on this new chain? It should come to your attention that by doing this simple branching, you've effectively created a new cryptocurrency. In this case, the "forkers" called it Bitcoin Cash .

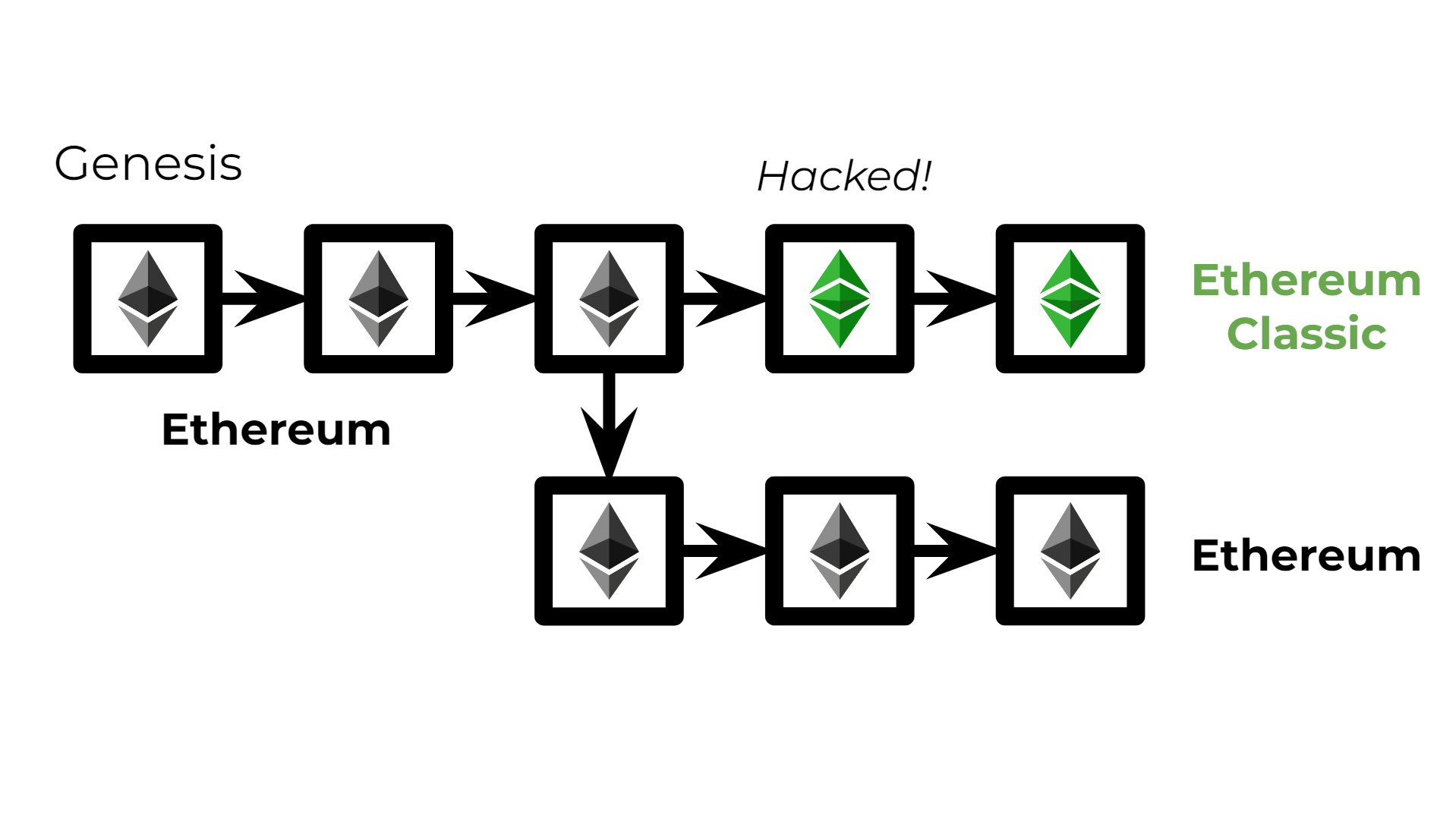

- Mind you, forking isn't some kid-in-their-dad's-garage practice which just produces an "alt-coin": the Ethereum network was hacked once, which lead to the theft of a lot of ETH. In this case, the majority of the network decided to make a hardfork to revert the theft. The hardfork is now the actual Ethereum blockchain, whereas the original chain is now known as Ethereum Classic .

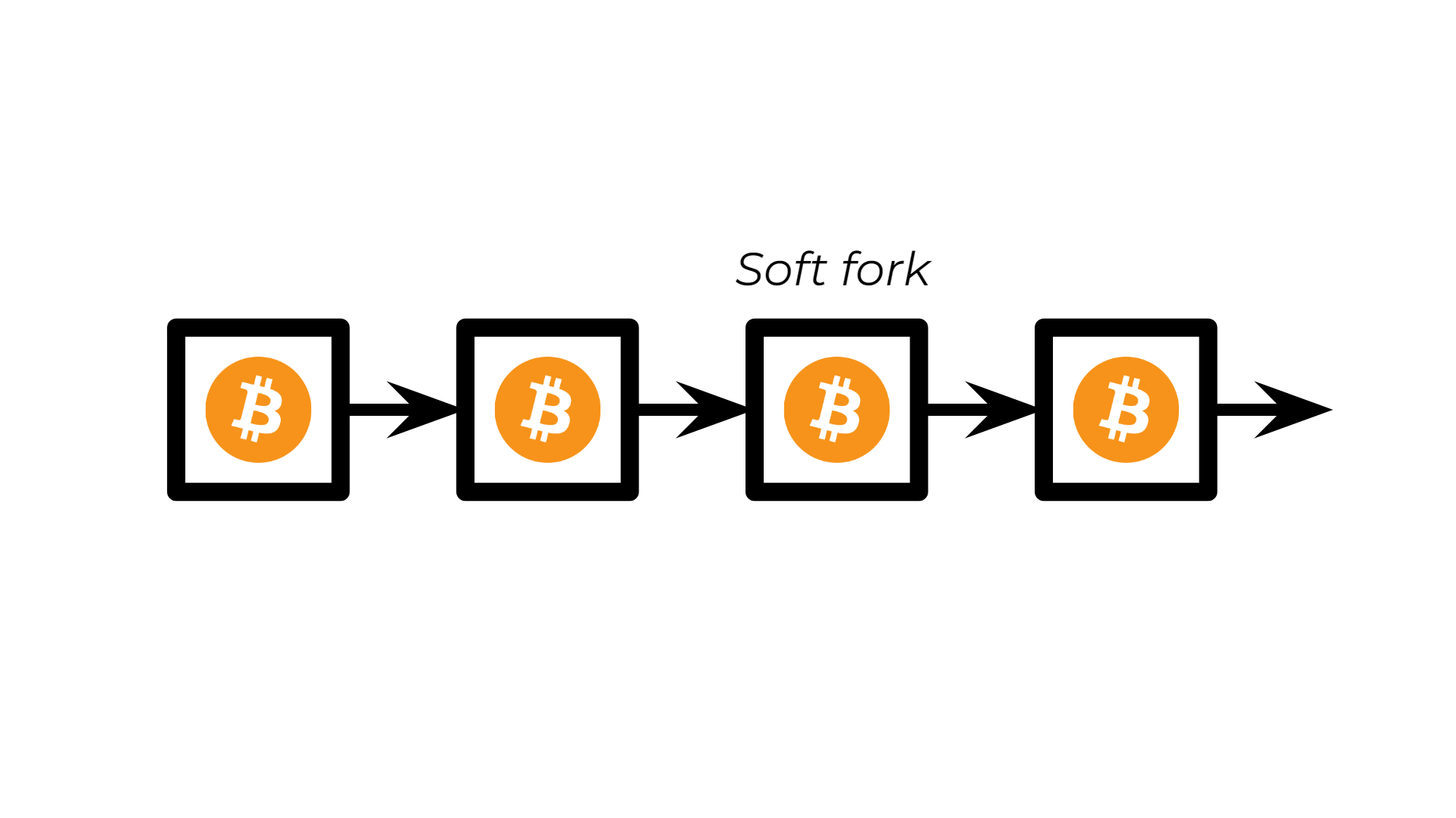

- A soft fork is usually a change that's less invasive and is accepted by all members of the network, it doesn't create a new cryptocurrency.

- Mining would seem like a pretty useless task in the protocol we've implemented. After all, you're giving up electricity for free and losing computing power. The original Bitcoin whitepaper addresses this, and gives two mechanisms to solve it. First, miners can add a particular transaction at the beginning of each block granting them access to newly generated coins. The amount varies, and in the Bitcoin protocol it halves every 4 years (now it's at 6.25 BTC, and there'll be a halving in about a week). Second are miner fees: each miner gets a small portion of every transaction in the block. Remember about our arbitrarily chosen 5 transactions-per-block and every-hash-starting-with-two-zeros? Well those are crucial factors to how a cryptocurrency behaves. It's all about those miner fees. If a protocol requires a hash starting with a lot of zeros and allows very little transactions per block, then each block is going to be very valuable. The fees set be the miners are going to skyrocket because of simple supply and demand. That's why Bitcoin fees are so high: Bitcoin's block size can contain around 2000 transactions, and a block is mined in about 10 minutes (in comparison, Visa processes about 65.000 transactions every second ).

- In general we want to keep our transactions private, such as in our bank account. Bitcoin takes a different approach: every action is public, however, those actions can't be linked to your identity. As you've seen, transactions are made between keypairs, so if your keypair is not tied to your identity in any way, then nobody will know that any transaction you made was yours. This seems quite smart until you realize that you can't use bitcoin to buy your groceries. As long as that's true, you'll have to exchange your bitcoins for fiat, and there's the trap. Normally bitcoins are bought in exchanges: systems that connect BTC buyers with BTC sellers. Those exchanges usually require identification through passport, pictures or whatever, tying your identity to your public key. Anyone can then grab your public key and search where you've sent money. There are ways like cash by mail in decentralized exchanges, but perfect privacy is more difficult to achieve than initially thought.

- There are some clear flaws (or features?) that might be interesting to tweak, which gives rise to a grand variety of so called "alt-coins" that do so. To solve the problem with fees, Litecoin reduces the mining time of each block to about 2 and a half minutes. To solve the problem of privacy, Monero has some interesting features that have made it pretty much untraceable. Other protocols such as Ethereum focus on how blockchain technology can be applied to concepts other than currency, like contracts.

I hope you gained some insight!

References

- Bitcoin Whitepaper

- Bitcoin Core, GitHub

- How do Bitcoin clients find each other

- How to become a DNS seed for Bitcoin Core

- Code is Law, Ethereum Classic

- Litecoin

- Monero

14/04/2024