LSD, death and resurrection.

There was this thing in my highschool where you had to spend a year or two researching about some topic of your choice and write a 30 page essay about it. So me being myself, I immediately came up with a series of dumb ideas to toe the line between good and evil, like synthesizing methamphetamine from paint thinner (don't ask).

In the end these were brief enough to not make up a full document, but one of them did stick around: LSD.

I was amazed by the stories of people who had taken it and narrated its effects. Also the fact that it had been used in therapies and could be used again. So I started researching. I had had a turbulent year, so I ended up finishing the project in about 5 months. The result is this:

LSD.pdf

(Warning, it's in spanish).

Highlights

How LSD works

The brain has a series of "filter mechanisms" with which we process the world. Right now millions of photons of different wavelengths are impacting your eyes, you are hearing the fan of your computer or someone speak or the sound from your headphones. You are feeling your clothes on your body and your body on your seat. Even with all those stimuli, you are able to focus on one thing: this text. Your brain effectively filters all the non-relevant information, allowing you to focus.

The current theory on how LSD works (and other serotonergic hallucinogens such as mescaline and psilocin) is that it interacts with the Serotonin system in a way that causes downstream alterations that in the end interfere with these filter mechanisms. When this happens, all of those photons that you ignored, all of the sounds that you thought of as unimportant, all shapes, all colors, everything goes unfiltered. This is interpreted by conscience as hallucinations, but it also has psychological implications. One of the first uses of LSD was in therapy, as this "sprouting" of sensations could be used to liberate repressed material in patients suffering from trauma or similar. Keywords: psychedelic therapy.

Phármakon

Phármakon is a Greek word used to designate a substance that works both as a poison and as a remedy. What distinguishes then that the substance acts as one or the other would be the dose. This is Paracelsus' Sola dosis facit venenum (only the dose makes the poison).

Doses of 5 miligrams of the substance amphetamine are used in treating ADHD (see Adderall ), doses of 20 to 50 mg are used for recreational purposes, and ones higher than 200 mg are considered lethal. Once again, the dose makes the poison (and the remedy).

Active principle

When consumed, some plants produce powerful effects on the body. We have already understood the concept of phármakon , but at a fundamental level these effects aren't caused by the whole plant, but by a very specific molecule. For example, from the Coffea plants we get coffee beans, which we use to make coffee. Coffee is great and lets us inhibit our fatigue perception, however that effect isn't produced by all of coffee, but by the molecule caffeine . Caffeine is said to be the active principle of coffee. We can isolate caffeine and compress it into tablets with exact doses, and we've invented medicine.

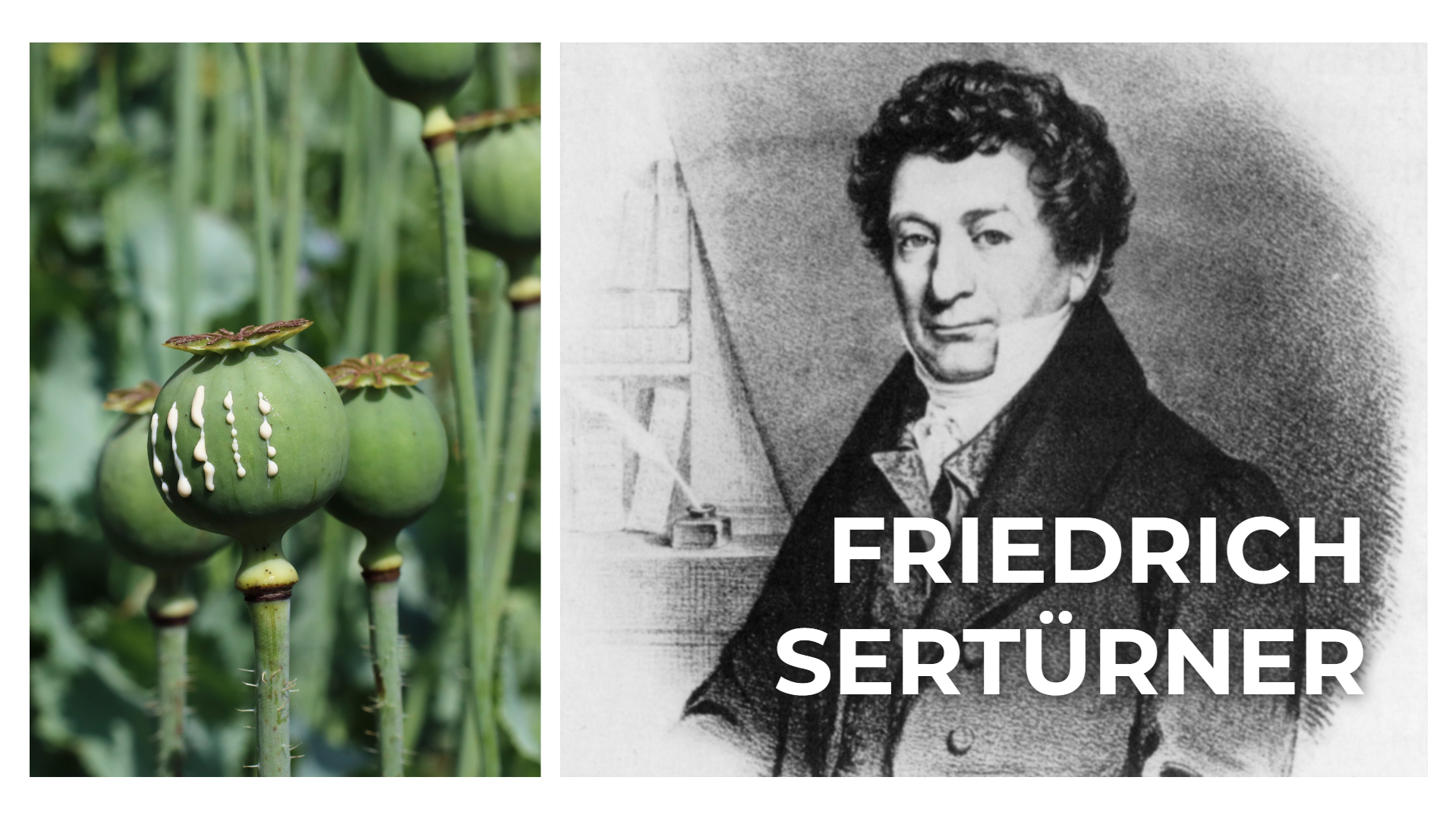

The idea of taking the active principles of different plants to get medicines starts a revolution in the XIX century which persists until now. One of the first instances of this happening is the isolation of morphine from opium by F. W. Sertürner . This isolation was crucial: opium from Afghanistan may not be as strong as opium from Turkey, but 10 mg of morphine will produce the same effects here and in Japan. Furthermore, morphine can be injected to produce instantaneous effects. Eventually this trick of going from the living thing to the active principle would be done by Albert Hofmann on the Ergot fungus , yielding lysergic acid, from which LSD was derived. Modern medicine is born.

Addiction

The neurological mechanisms governing addiction are complicated, but we can see some patterns. I would have to distinguish between two types of addiction (I don't think this is done in any manual or paper, but it's a useful distinction).

- The organism has a capacity to adapt to exogenous substances. Taking several doses of aspirin in a week generates a kind of "resistance" to it, resulting in less effects. This "resistance" is called tolerance , and it implies a series of metabolic adjustments inside the body. When stopping the consumption of aspirin, these metabolic changes result in a set of measurable symptoms known as withdrawal syndrome . One example is opioids. If we want to relieve some pain, we may take opioid medicine (like codeine or vicodin). However if we do that on a daily basis, our body might adapt to the medicine in a way that renders it useless. If we now stopped taking the opioids, that adaptation would cause us to feel pain. This new pain isn't the result of the original disease, but a result of withdrawal. This is important, as a person suffering from withdrawal syndrome is more likely to look for more doses, but it's not the only variable.

- In our brains there are some neural pathways closely related to reward (VTA, NAc...). Some substances interact with these reward systems, making them more powerful. Amphetamines for example interfere with the transport and release of dopamine, which is a neurotransmitter that heavily participates in these systems. When this chemically induced reward takes precedence over other natural rewards, problems may arise. The subject may pursue this artificial reward in detriment of biological need or personal motivations. This is anothes form of addiction, and it's controversial in the sense that it's hard to draw a line to determine what an "artificial reward" is. Compulsive shopping, gambling and other "natural" behaviours can also stimulate these reward pathways. Are they addictions? It's hard to say. We tend to study these things through animal models, and we can't analize how a rat would get addicted to shopping.

Science

Scientific knowledge is a fractal. Looking at documentaries and science communicators it can be easy to forget that they make huge simplifications. One of my favorite examples is chemistry. We are taught to think in atoms, but never get to see one. Sounds weird, right? Saying "But you can't see atoms!" seems like something a flat-earther would say. But in the end that's what scientific knowledge is about, questioning and going deep into experiments. It's just that it's so much that we shorten it and just get to the point, making assumptions and simplifications in the process. Same thing applies some levels of abstraction upwards. It's easy to say that "we have linked addiction to a series of dopaminergic pathways in the brain", but actually going through the research to be sure of that statement is one hell of a task.

Don't trust any opinion until you've gone to its roots. This world is a soup of conflicting interests, and people will naturally try to drive you this way or the other. It's OK to fictionally engage in an opinion as a way of socializing, but at a fundamental level you must remain neutral. This teaches us to be prudent and not participate on heated arguments unless convinced, as acting otherwise would be morally inconsistent.

Bibliography

In my journey I would have to underline the importance of several sources:

- Principles of Neural Science , by Eric R. Kandel et al. During some weeks my life consisted on waking up, going to school, going to the library and reading this book, page by page, until the library closed at night. It gave me a general understanding of the brain and how exogenous substances act on it, and also the neural bases for behaviour and addiction. I must admit I haven't used 70% of the information in here. To this day I'm not sure how it's going to be useful to know that "Glycine is a cofactor in the activation of NMDA receptors" in the near future. To be clear, I know this book is meant as an index to consult whatever you need, but I wanted to get a truly deep understanding.

- Ergot and Ergotism . Narrating the history of ergot to as much detail as possible. It was my first insight in what it looks like to do historical research, and I've acquired an insane amount of respect for historians after this.

- LSD - My Problem Child , the story of LSD told by its own creator, Albert Hofmann. From its accidental discovery to its use in arts and psychotherapy to the widespread of the hippie movement and its prohibition. What can I say, it's just a wonderful book.

- Antonio Escohotado's figure in general has had a huge role in my writing process. I haven't actually taken much information from his books, but his spirit definitely permeated my views and thoughts on the topic. Robert Sapolsky is another man I admire for similar reasons.

Anyways, I could keep rambling about Huxley's Death Trip or Alexander Shulgin's psychedelic experiences , but I think you get the gist of it. Onto other things.

19/03/2024